Reading Music Notes: The Beginner’s Guide

Want to learn the basics of reading music notes? Look no further! This guide teaches you everything to get started.

Regardless of natural talent and ability, learning to ‘speak music’ opens up a world of communication between you, your instrument, and anyone you jam with.

However, learning to read a new language can be intimidating.

We get it.

At first glance, music notation can look like some kind of alien hieroglyphics.

But don’t fret.

This guide walks crop circles around music theory, so you’ll be reading music notes in no time!

Pitch and notes.

Music is a language of sound. The first thing for a beginner to learn is interpreting and contextualizing musical sounds.

When an instrument produces sound, it vibrates at a particular frequency or pitch.

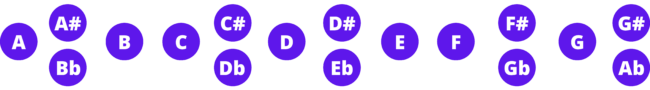

In Western music, there are twelve specific frequencies we call notes. These twelve notes repeat themselves across higher and lower registers of pitch.

The letters A to G represent seven of the twelve notes, while sharps and flats account for the remaining five. The sharp (#) symbol means that a note is slightly higher and flat (b) slightly lower.

The grand staff.

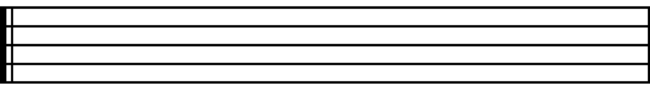

As you can see below, a staff is a stack of five horizontal lines.

If there are five lines, there are four spaces between them. Each line and space represent a note, with the low notes on the bottom lines and the high notes on the top.

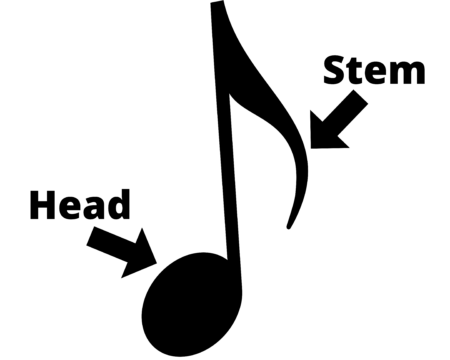

Notes on a staff appear in various ways, but all of them have some kind of circle and sometimes a line.

The line is called a stem. It could be straight, curly, or not there at all. The circle is the head, and it could be full or empty. These will determine the rhythmic value of the note. You can read more about reading sheet music here.

The grand staff has ten lines altogether, split into two groups of five.

We generally use the grand staff for instruments that can express a wide range of pitches or music that requires two separate but simultaneous parts, like using both hands to play the harp or piano.

The note middle C note, which is more or less at the center of the keyboard, sits in between the two staffs on a ledger line (we’ll get to that soon).

The treble clef.

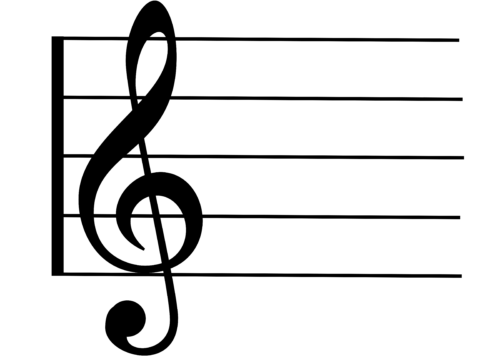

A clef symbol appears on the far left side of the staff. It indicates which note falls on which line. The range of your instrument determines the clef you use so that the notes are in the right places.

For piano, you use the treble clef for music you play with your right hand or other instruments that play music in a mid-to-high register.

The center of the circle of the treble clef sits on the second line from the bottom of the staff and indicates the note G. This is also known as the G clef.

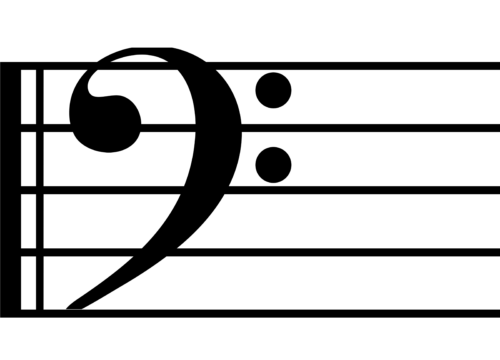

The bass clef.

We use the bass clef to write music for instruments with a lower register, such as the piano’s left hand or a bass guitar.

The line between the two bass clef dots is an F below middle C. This is why it’s also known as the F clef.

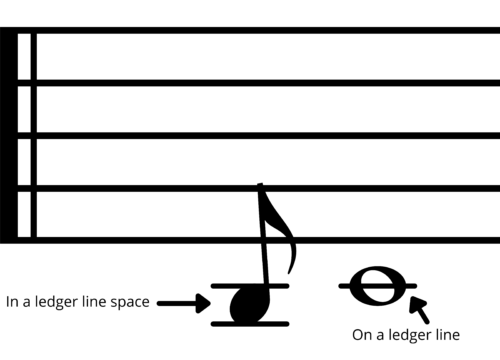

Ledger lines.

Sometimes when you’re reading music on the staff, you’ll notice that the notes go higher or lower than the lines. These are ledger lines.

To make them, draw a note head either above or below the staff, then place a line through, above, or below the note head.

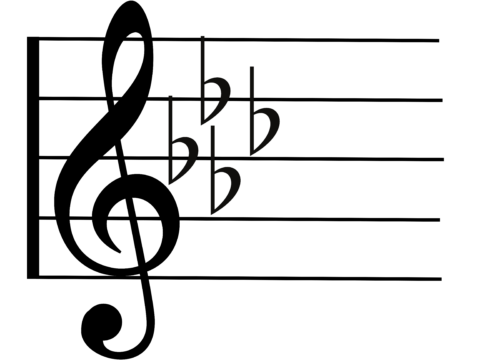

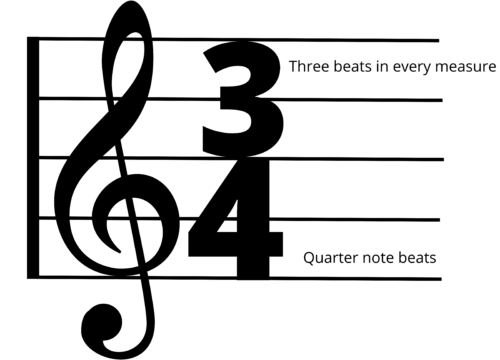

Key and time signatures.

There are two more crucial pieces of information at the beginning of the staff and to the right of the clef.

The first is the key signature, which tells you how many sharps or flats are in the music. If a sharp or flat appears in the key signature, it will not appear in the notes. If the composer adds an extra sharp or flat beyond the key signature, it will be written with the notes.

The time signature will be to the right of the key signature, just before the actual notes appear. This indicates the division of rhythm in the song, alongside the bar lines, which create vertical divisions of the horizontal staff lines to group the notes according to rhythm value.

The top number of the time signature is the number of beats per bar. The bottom number of the time signature is the type of beat (half note, quarter note, eighth note). You can read more about time signatures and key signatures here.

Reading music notes all by yourself.

Music is, first and foremost, a phonetic language. It’s all about the sound you hear (except for Beethoven) and the sound you produce. In the same way, you don’t need to be able to read or write English to speak, you don’t need to be music literate to play an instrument.

But without musical literacy, it can be difficult to communicate in a common language.

Music theory teaches you to read and write music independently, communicate clearly with other musicians, and stretch your creativity beyond natural abilities.

Is there an app for that?

Discover a custom plan that’s put together for you by in-house musicians who put fun first in every lesson. All it takes to get started is an interest in learning music and a few minutes to check out Simply Piano.