Ear Training for Beginners

If you want to develop musical magic powers, these tips and exercises can help you get started with ear training.

An artist develops their eye, and a masseuse their touch.

But a musician?

You have to make your ears grow.

Well, not literally.

Ear training is about practicing the art of listening, understanding what you are hearing, and eventually speaking the language.

Pull out your instrument or instrument app while you read and get ready to learn!

What’s ear training?

Have you ever witnessed a musician hear a song for the first time and then just play it?

It can seem daunting or unattainable, but every musician has been through the trenches of ear training to get to where they are. Like a language, ear training connects what you hear with what you know. It is about attributing meaning to sound and then identifying that meaning when you hear the sound.

To put it less philosophically, it is about recognizing pitches and their relationships.

Pitches and notes.

Sounds vibrate at specific high and low frequencies called pitch.

There are twelve common frequencies, or notes, in Western music. Each note has an equal amount of space between it and the next and repeats itself in higher and lower registers of pitch.

We name these notes with seven letters. The other five notes are either slightly higher in pitch, sharp (#), or slightly lower in pitch, flat (b).

- A

- A#/Bb

- B

- C

- C#/Db

- D

- D#/Eb

- E

- F

- F#/Gb

- G

- G#/Ab

Hearing these twelve notes in any register is the first and most crucial step in developing a musical ear. The test is if you can listen to notes and sing them back correctly.

Ear training exercises.

- Play a note on any instrument or instrument app, and try to sing it back! You should hear when the note is correctly in tune. If you don’t, having a friend with you would be good – someone whose ear you trust.

- Listen to a song you love. Choose one line of the melody, and see if you can figure out how many different notes it has.

Intervals and melodies.

Once you can hear notes, you start to pay attention to their relationships. These relationships form because of the space between the notes, called intervals.

The smallest interval in Western music is called a semitone. This is the space that separates each of the notes from one another.

The biggest interval, which separates a note in a lower pitch register from the same note in a higher pitch register, is called an octave. An octave’s space contains all possible interval relationships, and each has a unique name.

It looks something like this:

Perfect Unison (the same note twice) = A → A

Semitone/Half-step/Minor 2nd = A → A#/Bb

Tone/Whole-step/Major 2nd = A → B

Minor 3rd =A → C

Major 3rd = A → C#

Perfect 4th = A → D =

Tritone/Augmented 4th/Diminished 5th = A → D#/Eb

Perfect 5th = A → E

Minor 6th = A → F

Major 6th = A → F#/Gb

Minor 7th = A → G

Major 7th = A → G#/Ab

Perfect Octave = A → Higher A

So how does this have anything to do with your music?

The heart of every song is the melody. This is what the lead singer or lead instrument plays. It is often put to words, and it is the song’s most recognizable and memorable element.

A melody is a series of notes with different intervallic relationships that you play one after the other. You can practice hearing intervals and find them in songs with the ear training exercises below.

Ear training exercises.

- You can recognize and remember every interval by connecting it to a song you know! All you have to do is sing or play the first two notes of the song to hear the interval. Then the music becomes a reference point for singing, playing, and identifying the intervals.

- Semitone/Minor 2nd: Jaws theme

- Tone/Major 2nd: Happy Birthday

- Major 3rd: Kumbaya

- Minor 3rd: Smoke On the Water

- Perfect 4th: Here Comes the Bride

- Tritone: The Simpsons theme

- Perfect 5th: Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star

- Minor 6th: Lchaim, To Life! (Fiddler on the Roof)

- Major 6th: My Bonnie

- Minor 7th: Star Trek theme

- Major 7th: Don’t Know Why (Norah Jones)

- Octave: Somewhere Over the Rainbow

- Take the melody of your favorite song. Choose a few lines, and practice singing only two syllables or notes at a time. Use the interval song as a reference to figure out which interval you are singing, then write it down. Do this with every pair of notes in the lines you’ve chosen, and you will start to understand how melodies depend on intervals.

Scales and chords.

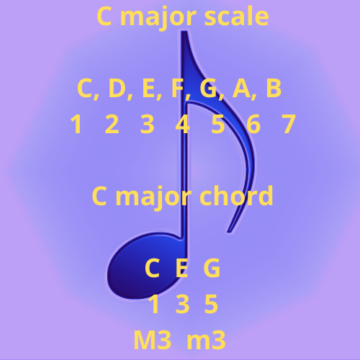

A scale combines seven notes, one after the other. The unique pattern of intervals between the notes gives each scale its personality. The best scale for beginners to learn is the major scale.

For centuries, the major sound has been the essence of music in the Western world. Major scales contain all major and perfect intervals and only have semitones and tones (two semitones).

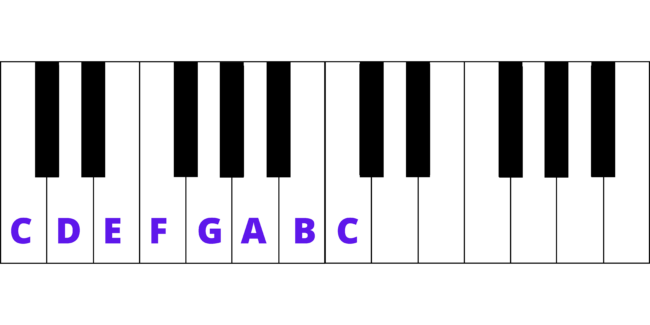

Let’s make a major scale starting on C as an example. If you have an instrument, play along:

Once we’re familiar with the sound of the major scale, we can start to listen for chords.

A chord is any combination of two or more notes you play simultaneously. Most chords are triads (containing three notes), but more complex chords can have five or even six notes.

Chords create the musical element we call harmony, the relationship between notes you play together. Learning to hear harmony is about understanding the mood and character of each type of chord.

Major and minor chords.

You can build major chords from the first, third, and fifth degrees of any scale and two intervals – a Minor 3rd (m3) and a Major 3rd (M3). Major chords are often “happy” because their sound is light, bright, and full.

A minor chord is like a major chord with the third degree flattened (lower by a semitone). This means it’s got an m3 interval followed by an M3. You can recognize it by its gloomy, melancholy sound, which evokes sadness and fear.

Let’s build a major and minor chord, starting on C:

Don’t forget to check out our ear training exercises below to practice hearing scales and chords. Before that, here are a couple of other ear training terms:

Active Listening

Sometimes we can walk into a room and miss half its objects at first glance. In the same way, when we listen to music, we are usually pretty checked out. We allow the groove to move our bodies, or maybe we even let the music help us feel something we had suppressed.

But active listening is about applying our theoretical and analytical mind to what we hear. It’s also about listening to music as an activity in and of itself – not in the background while doing something else.

Once you have practiced the ear training exercises, try listening to one of your favorite songs and identifying different notes, intervals, scales, and chords!

Perfect pitch vs relative pitch

So remember when we spoke about notes and pitch? Perfect pitch is the ability to hear any note, identify it by name, and replicate it perfectly. Relative pitch is the ability to sing or identify any note someone plays and names for you.

The best way to understand this is by using the analogy of color. Somebody with perfect pitch can identify a note they hear in the same way you can see the color red and know that it’s red.

Somebody with relative pitch is like determining what is red if first you are shown what it looks like.

Ear training exercises.

- Choose a note that feels comfortable or familiar. Write down all the sequential notes of the major scale by using the pattern of tones and semitones described above. Sing or play the scale to familiarize yourself with the sound. Repeat this exercise starting on all twelve notes. By the end, you’ll be able to sing a major scale without any point of reference! An excellent song to help you with this is “Do, a Deer” from “The Sound of Music” – it is all about learning the major scale.

- Put on your headphones and throw on your favorite song. Listen to the first line of the music on repeat a few times. See if you can identify whether the chords are more “bright” or “gloomy.” Write down the pattern of the first four chords as you think you hear them, just by writing major or minor. Check out the chords online to see if you were on point!

- The best way to discover chords is to start experimenting. Sit at your instrument (it needs to be a piano or guitar for this) and begin combining notes into groups of three. Write down the names of the notes you included and how the chord made you feel. Don’t worry about the chord’s name – just listen closely to its character and even give it a fake name if you like! This is the best way to understand how to use chords in music.

Practice makes perfect.

If you create a consistent practice routine with these exercises, you will indeed find that your ear has developed. Suddenly you’ll hear a song on the radio or in a restaurant and say, “Hey, this has a major sound!” or “I think I heard a perfect fifth at the start of the chorus!”

Before you know it, you will have ample tools to communicate with other musicians, play songs by ear, and even create music.