What are Diatonic Chords?

Want to play diatonic chords? You’ll need to master the major scale. This article explores all possibilities for making diatonic harmony.

The word diatonic means “strictly within a key.” Diatonic harmony is all about using only the notes of a particular scale to create chords. This is one of those situations where limiting your options can open up creative freedom. In other words, if you restrict yourself to seven notes, your inspiration can blow wide open!

But diatonic chords are about more than just knowing which notes to use. Each degree of the scale has a specific harmonic function because of its relationship to the “one chord,” otherwise known as the root or tonic. This article looks at diatonic harmony in the major scale.

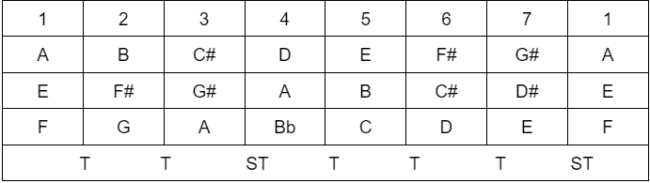

The major scale.

The major scale is a series of seven notes with specific distances between them. The degrees of the scale are from one to seven. You can apply their intervallic pattern of tones and semitones to create a major scale starting on any note. This is the formula, with examples in A, E, and F major:

If you’re a little rusty, you can Quickly Learn Piano Notes and Chords for a speedy review.

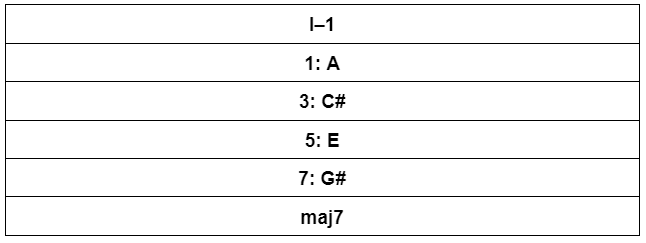

The tonic = Imaj7.

The tonic is the scale’s root note and how it gets its name. For example, in A major, it would be A. This is sort of the axis on which all the other notes turn. The note feels like arriving home in the context of a song or melody.

If you’re playing an utterly diatonic song, you should be able to identify this chord quite easily. If the song has key modulations, the feeling of arriving home keeps changing like some nomadic ex-pat. When you build diatonic chords on the tonic, you have a major triad or a major 7 chord.

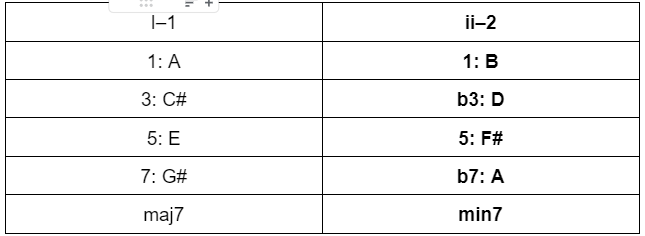

The supertonic = iim7.

This is the second degree of the major scale. It is known as the supertonic because of its proximity to the tonic. Its sound is recognizable because it leads intuitively to the five chord. This creates the famous chord progression of ii–V–I.

The supertonic is always minor or minor 7 in its diatonic context. In the key of A, it’s Bm7.

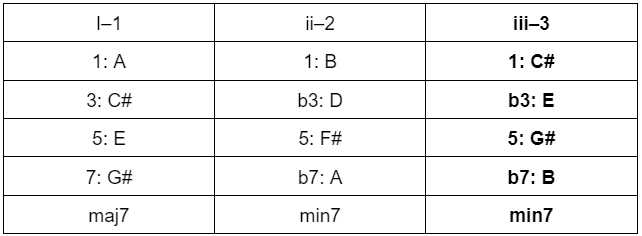

The mediant = iiim7.

The mediant is the third degree of the major scale. In Latin, this word means ‘middle,’ and it has this name because it is the middle note of the major tonic triad.

For example, this note is C# in the key of A. If you build a chord on the mediant, it will also be minor or minor 7. It is closely related to the tonic and the dominant, as it shares two notes.

Check it out:

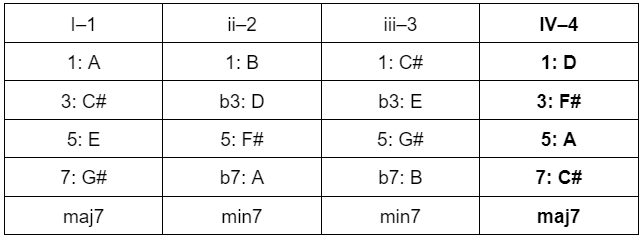

The subdominant = IVmaj7.

Don’t get too excited. There is nothing kinky about this. It’s just another name for the fourth degree of the major scale.

The subdominant gets its name because it has a gravitational pull towards the tonic, just not quite as strong as the dominant’s. Another reason is that it is a fifth below the tonic, making it a long-lost dominant cousin.

A prevalent progression is IV–V–I. The transition from the four to the five creates a gradually increasing tension, which resolves when it arrives home at the tonic.

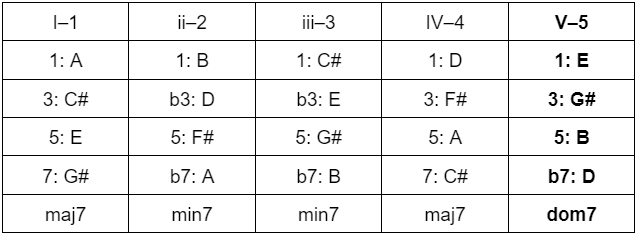

The dominant = V7.

If you believe that the world is balanced between good and evil, you could say that diatonic harmony sits in a balance between the five and the one, or the dominant and the tonic.

Nothing can resist the tension created by the dominant–it just screams to be taken home to the tonic. It is a powerful musical tool that has become so familiar to the Western ear that if you were to sing a dominant chord to any average non-musical person, they would surely be able to sing, or at least sing in the direction of resolution to the tonic. For example, in the key of A, the dominant chord is an E7 (which has a flat seven and is known accordingly as dom7).

There is an apparent reason for the dominant’s tension: the semitone movements that happen in the transition from the five to the one chord.

The third degree of the dominant chord resolves to the one of the tonic chord (e.g., G# to A), and the flat seven of the dominant chord resolves to the third degree of the tonic chord (e.g., D to C#).

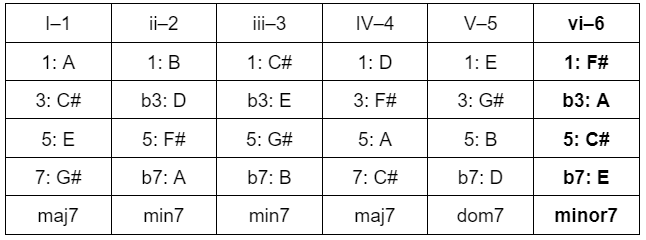

The submediant = vim7.

This is the sixth degree of the major scale. We call it the submediant because it is a third below the tonic (like the subdominant is a fifth below the tonic). This gives it a mediant-like relationship to the tonic in certain contexts.

The submediant, or relative minor of the tonic, shares two out of three notes in the chord. Think of it as the tonic’s gloomy teenage brother. Or bitter old uncle. (Or whatever.)

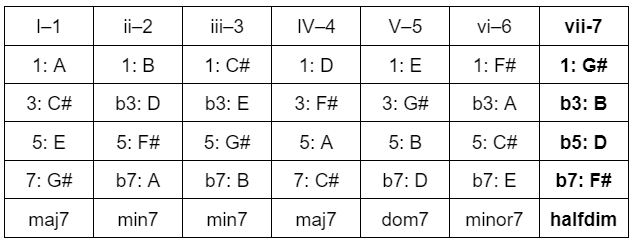

The leading tone = vii(halfdim).

If you thought the dominant was tense, you might not be able to handle the leading tone. This is the seventh degree of the scale, and it’s like a dominant chord on steroids.

Its tension is arguably stronger than the dominant’s because the root note of this chord is a semitone below the tonic (the third degree of the dominant chord), making it irresistibly close to resolution.

It is always a half-diminished chord, which is extra dark because it has a flat third, fifth and seventh note. This is a great chord if you feel like you’ve used the five chords a few too many times.

Don’t be a goody-two-shoes.

Understanding the inner workings of functional and diatonic harmony is super important as a foundation. But make sure you don’t become afraid of breaking the rules.

What makes music beautiful is the moments that take you by surprise. Don’t be the chord police–stay true to your internal artist and make sure you use technical knowledge to strengthen your creativity, not quash it.

For an interactive teacher conveniently app-sized–try out Simply Piano.